Setting the stage

Heads Up!

This article is several years old now, and much has happened since then, so please keep that in mind while reading it.

Public speaking can be a daunting experience, even in front of half a dozen people let alone a round century of them. Rationally, you know there is no physical danger - you will not be chased or hurt or injured, there is no reason for your heart to drum in your throat or anxiety to tremble in your fingertips - but knowing it is so, does not necessarily solve the problem.

In the history of human endeavour there are a few situations that have always proven to spell trouble, and our cognitive revolution has not dampened the hardwired fear of these situations...

- Being in a wide, open space with nowhere to hide

- Having the sole attention of a number of individuals

- Having no weapon or defensible position available

Generally, if you were in the wild jungles of ancient man, on your own, and found yourself in this situation, then there was a pretty high chance that you were about to be eaten with only your own teeth and nails to stop that from happening. Coincidentally, public speaking also ticks all of these boxes: so that hammering heart makes a bit more sense now, eh?

But, why would I want to give a presentation?

So first off, being afraid of public speaking is completely natural - you're not weird. But also, we probably shouldn't let our fears (especially those from a bygone era) control and manipulate our present.

Secondly, fear is not always a bad thing. Yes, being scared of heights or bears or infectious diseases is generally wise and will keep you alive and kicking, but fear of public speaking falls into the "somewhat irrational" category.

Some of my favourite projects were those that when I initially started on them terrified me. How was I going to do this bit? How was that bit going to work? How should it be extended, maintained, structured? That fear meant that I was testing the limits of my knowledge, but that fear also meant there was an opportunity to grow in technical experience and confidence. Fear can be useful and facing it can be a reward in itself, so don't let the fear of public speaking stop you from sharing yourself.

Making and delivering presentations is both challenging and rewarding, even if the reward is simply being brave enough to do so. We live in a knowledge-sharing world, especially in technology, so being able to express your ideas to others and soundly wrap them is an important skill to master. I am going to take you through my own presentation preparation method and how I refine and improve my work, in the theory that something might gel with your own way of thinking and either give you somewhere to start or something to improve upon.

What do I want to communicate?

It is broadly recognised that all presentations fall into one of two categories; either you are trying to train your audience on a particular topic e.g. technical demos and code, or you are trying to persuade them to a particular point. The first step is to decide which of these would best serve your purpose.

So before we start the planning journey, you first need to know the gist of what you want to say. Anyone who has ever tried to plan out fiction will recognise this as the "premise" where you condense your plot into one handy, punchy sentence. This is incredibly hard to do, and even harder to do well - I could show entire notebooks of failed attempts - but even done badly it is very worthwhile as it crystalises your thoughts into a concise and shareable sentence.

For example: "Give an insight into the neuroscience, psychology and cognitive processes that underlie problem solving."

Who should I talk to?

The demographic of the talk will depend upon who you are trying to teach or persuade. I find that it is helpful to settle on an individual that you maybe know or - if that feels too weird - make up a user persona like you would for a UX journey. That way, as you are planning content or conflicted on what to include in the talk you can keep revisiting your goal audience member with questions like, is that relevant to you? Would you find that interesting? Does that make sense?

For the "Debugging the Brain" talk I did at Umbraco UK Fest 2019, my assumptions were that the audience would consist mainly of problem solvers (possibly mostly programmers), but also that being technical wasn't a prerequisite to understanding the talk or content. You are faced with just as many problems in any other role, be it creative or logistical, and often without the defined "pat on the head" of yes-that-works that we enjoy in development.

It's also good to rule out who you're not planning to talk to. Again in the case of "Debugging the Brain", I was assuming there would be no neuroscientists or experimental psychologists in the audience; not because I didn't want them to be, but just because the talk content would have been well beneath their experience level.

Setting out your audience expectations early enables you to tailor and focus the content of your talk. Additionally, it allows conference/meet-up organisers to make informed decisions about how best to communicate your presentation to their members and to know whether or not you would be a good fit for their event. Not every talk will please all of the people all of the time!

Planning

Hopefully, by this point, you are somewhat convinced that using your voice would be a good idea and you have thought about what you want to say and who you want to say it to. Excellent work!

Now we are ready to begin some planning. I will take you through my process (specifically the one I followed for the "Debugging the Brain" talk as this process is slightly different from previous technical talks I have given) and you can use it as a jumping-off point, or even as a baseline for things you know wouldn't work for you. After all, it wouldn't do if we were all the same!

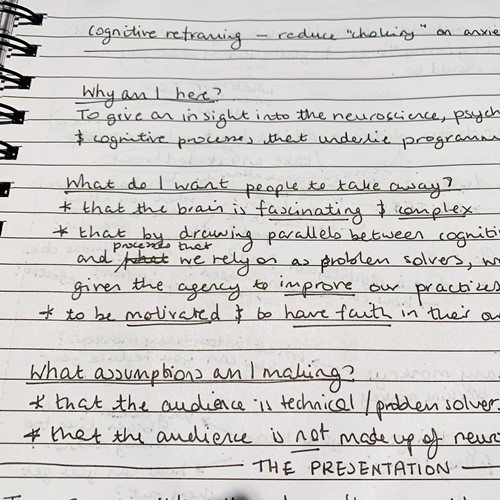

All my talk planning begins the same way:

- Why am I here? (What do I want to convey?)

- What do I want people to take away? (How do I want people to feel? What do I want them to know?)

- What assumptions am I making about my audience? (Do they need any additional contextual information in order to take away what I want them to?)

I use the premise I have already defined to answer these questions, and end up with something that I can focus on when I need to make decisions on resources or slides.

Raw resources

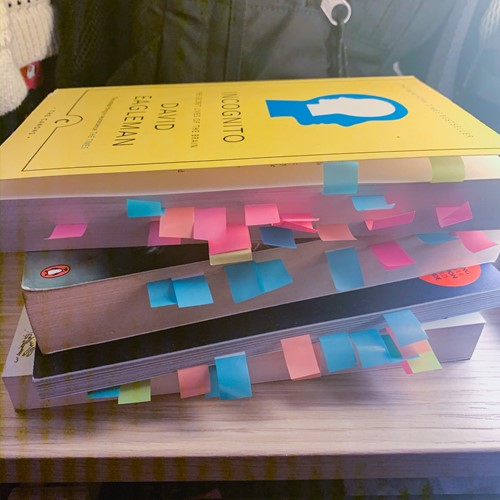

The next step for me is to start compiling my raw resources - for "Debugging the Brain", the raw resources looked a little like this:

But for technical talks, this is usually a demo or code repository which I will step through to extract the important code sections I need.

Getting a top-down view of the resources that will illustrate the points you want to make is super helpful because it allows you to start categorising them and plotting out a flow for the talk. Sadly, it is not always possible (or advisable!) to pack in every resource, no matter how attached you are to all of them. Sometimes a resource or area just won't fit with the overall narrative of your talk so you'll need to bench it for the timebeing. This isn't the end of the world; maybe it will form the basis for a future talk!

This is arguably my favourite part of talk-prep because you get to revisit all the things you've found interesting, or worked on, and you also start to get a good view of your current understanding of the premise that you want to present. This premise is essentially the core of what you have to offer to the audience; of what you want them to takeaway. At this point, the talk also starts to take shape within my mind's eye, a bit like a reflection shimmering into focus.

It is worth noting that if the talk is not coming into focus here, you need either more or fewer resources or possibly to revise the premise for what you are hoping to communicate. I have abandoned a few talks at this point because, without a clear view of how I'm going to illustrate my points, it becomes increasingly difficult to plot a coherent, sequential course for the flow of the presentation.

Defining flow

Defining the flow for a presentation is an intense and unique process based entirely upon your preferences - for example: how you learn, how you visualise the future, how you create and combine resources or how you sequence data within your own understanding. For me, it is an iterative process and is remarkably similar to how I would go about painting a picture...

-

Outline. Block out sections of information that sit next to each other. Broad strokes of colour. I am not concerned with the details or the words, but with the overall view of the presentation and how it feels as it sits together. In practice, this was translating my chosen and categorised resources into a slide deck where each slide represented an area that I wanted to explore and the associated notes were every note that I had on that section. This made it easy to re-order the outline flow. Note: this was not the final slide deck but more of a master deck to control outline.

-

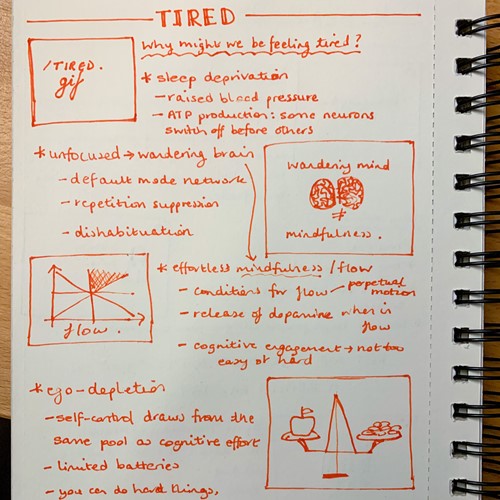

Visualise. Take a closer look at the information shapes; at how they form and sit together. How should they be defined? How can their meaning be best conferred? In practice, this meant taking my "master slide deck" back offline into a notepad and sketching out what slides might look like from an imaging perspective along with their key points. These do not need to be works of art, but we're just sinking some thought into how the ideas and points might look. If you are doing a technical presentation, a number of the slides might just look like code 😉

-

Sequence. This is where the concrete slide deck that I will actually present starts to take shape. With my outline and visuals in hand, I start to piece together the "real" slides - sourcing images, code and clarifying my text into focused statements that will fit comfortably on a slide. It's a good rule of thumb that if you're questioning whether a point should be on its own slide then it probably should.

-

Link. So we've got a slide deck and things to say... we're done now, right? Not quite! Our painting is starting to look great, but our shapes and colours have all been built independent of each other - now we need to show how they interact through shadows, light and tiny detailing. In presentation-terms this means we need to link our ideas together; for me, this means taking my content back offline and into the medium of flashcards. My main content items are highlighted on slides that all can see, but the shadows and light they refract as they flow together are all me and in the delivery of how I lead my audience between the slides. For me, these are the finishing touches and means that I'm ready to start saying my words out loud!

Practice

If compiling my resources are my favourite bit, practicing my talk is my least favourite part of the process. Rationally, there are a number of advantages to practicing a talk that I am uncomfortably aware of:

- Practicing a talk allows you to gauge timescales for when each section should be broached and wrapped up. It will also give you a good idea of whether you have too much or too little content

- Saying your work out loud will not only commit it better into your memory but will allow you to work out any sequential kinks that might interrupt your flow or make you lose your thread

- If you are feeling anxious, practice will assuage some of that nervous energy as it will demonstrate that you are more than capable of saying all the words you want to say and it will lend familiarity to the overall presentation

So the advice here is to practice, practice, practice - and next time I will almost certainly, definitely follow my own advice...

Delivery

Unfortunately, this bit is a little outside of the scope of this article (but I know you will do an awesome job!). There are a number of resources that you can use if you want to take the next steps but want some feedback or encouragement along the way:

- Look for a global diversity CFP day near you - these happen all over the world and are an amazing way to get into public speaking

- Get involved with something like #upfront which attempts to bridge the gap between being an audience member and a speaker

- Think of someone you've admired when they've spoken at a conference or event. Reach out to them: most people are happy to give advice or support through the Umbraco Community Slack or on Twitter if that's something that you need!

Useful Tools and Tips

- Invest in a hand-held clicker to move between slides. This frees you from having to stand near your laptop and allows you to move more naturally. Get one even if you never use it again; you can frame it for posterity for that one time you did a talk.

- Find a slide-writing software or app that works for you. I use a library called reveal.js to construct my presentations because it gives me complete control over styling/markup etc and, being a web developer, this makes me happy. Slides.com is the content managed version if you're not feeling the code side.

- I use Blinkist to gauge book content for relevancy to my research purposes. There's a lot of fluff out there and life is short - getting the gist of a book is a great way to know if it's something that you want to invest time and money into owning.

- I compile a lot of research notes on scientific papers, and have found a good way of storing this information is using something like MarginNote

- Find some note-taking software that works for you and allows you to express all of your complex, nuanced thoughts. I've found OneNote handy for compiling notebooks of mixed media and research as it has quite a flexible categorisation approach to storing notes and that pleases me.

- Plump yourself up when you are not feeling equal to the task. Remind yourself that you're not mad and this is worth it and that you have something you want to share! Compile a pre-talk music playlist that will lend you confidence when you need it most.

- Don't be afraid to rock it old-school: pen, paper, flashcards, etc. Computers are great, but play to your strengths, and use everything that you have at your disposal.

- Final tip: don't forget to smile on stage. Someone once told me that most people will almost instantly forget the content of your presentation, but they won't forget how you made them feel. Smile, try to enjoy yourself; even if people lose the thread of your communication they will leave smiling.

If you have any questions or want to reach out, you can always get me on the Umbraco Community Slack or on Twitter @lssweatherhead. I'm always happy to help!